From the Next Room

A new video experiment listening to a film playing in another room.

This was a trick we used to use in the recording studio; listening to a music track we were mixing from another space, essentially overhearing the music as it played in another room. It was an easy way to ‘disconnect’ from the process of working critically with the material, whilst at the same time engaging a different mode of listening, encouraged by the physical distance from the material, and the manner in which that distance reshaped the sound.

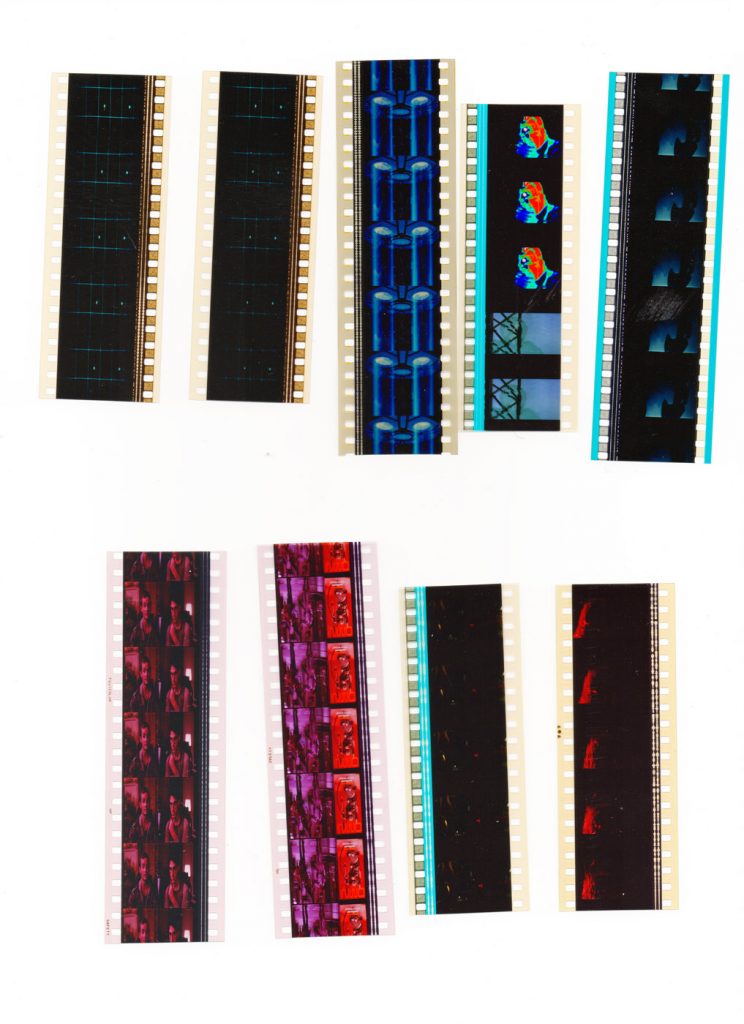

I set out to re-create this experience for a film and I felt that this scene from The Shining worked quite well, given how rooms feature so prominently in the film. The image I have used for background is taken from For All Mankind (Season 2, Episode 10), one of my favourite things on TV right now.

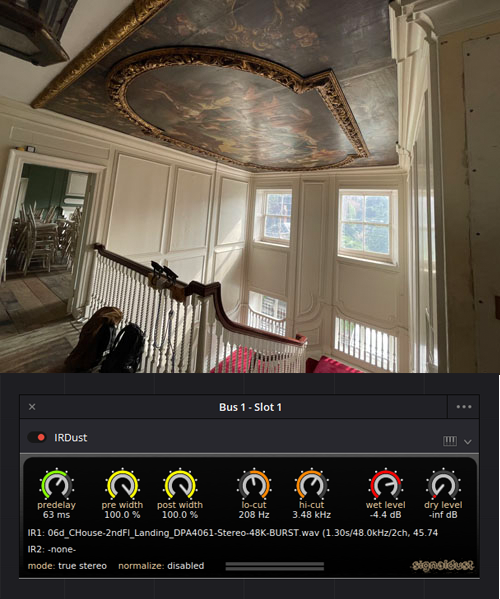

I decided against recording this overheard conversation for real (though I have done soundtrack re-recording in the past) but instead chose to use an Impulse Response to simulate the space of the room. An Impulse Response is essentially a sample of the acoustic characteristics of a particular space. To capture a response, a burst of sound or a sweep tone is played into the space and re-recorded. This recording is then processed to leave only the sonic characteristics of the space. The resultant Impulse Response can then be applied to any sound to give the impression of it existing in the sampled space. For this video I used a response from the wonderful free library A Sonic Palimpsest made available by The University of Kent. The image above shows a picture of the 2nd floor landing in the Commissioner’s House at Chatham where this particular impulse response was recorded. IR Dust is a software plugin which allows me to apply the response to the sound in my Resolve editing session.

I spent quite a bit of time experimenting with various impulse responses from this pack to tune the sonic spatialisation to my visual perception of the room (something which film sound professionals do all the time). Whilst I am happy with the ‘fit’ (marriage?) between sonic space and visual space, I’d be interested to hear how it sounded to you.