Super Volume – A Tactile Art

This is the second iteration of the Super Volume project. You can visit the project homepage here, where you will find links to all the outputs from the project so far. This page will focus on the video essay A Tactile Art.

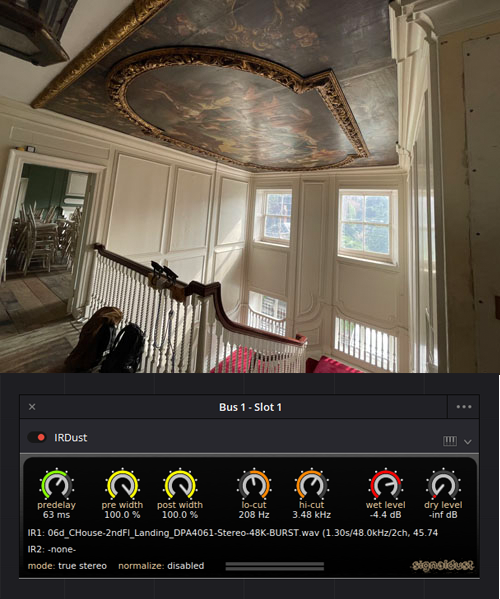

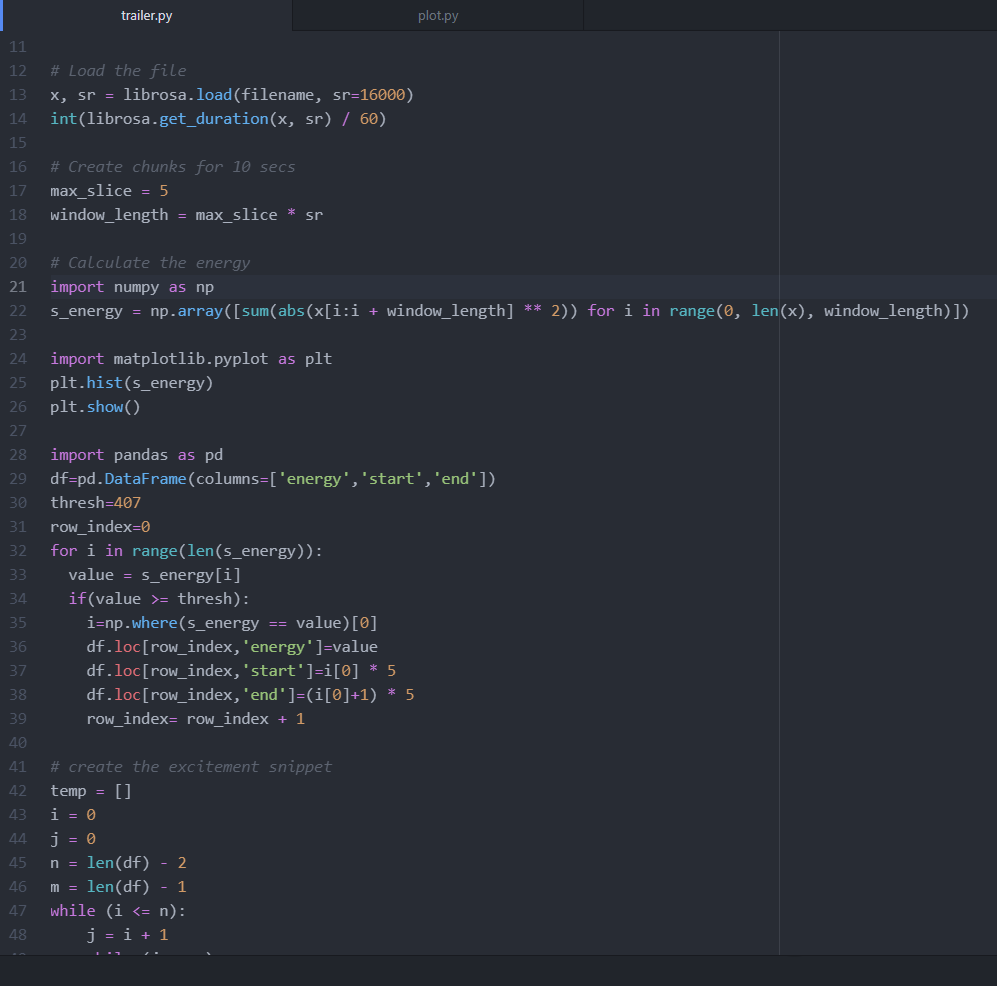

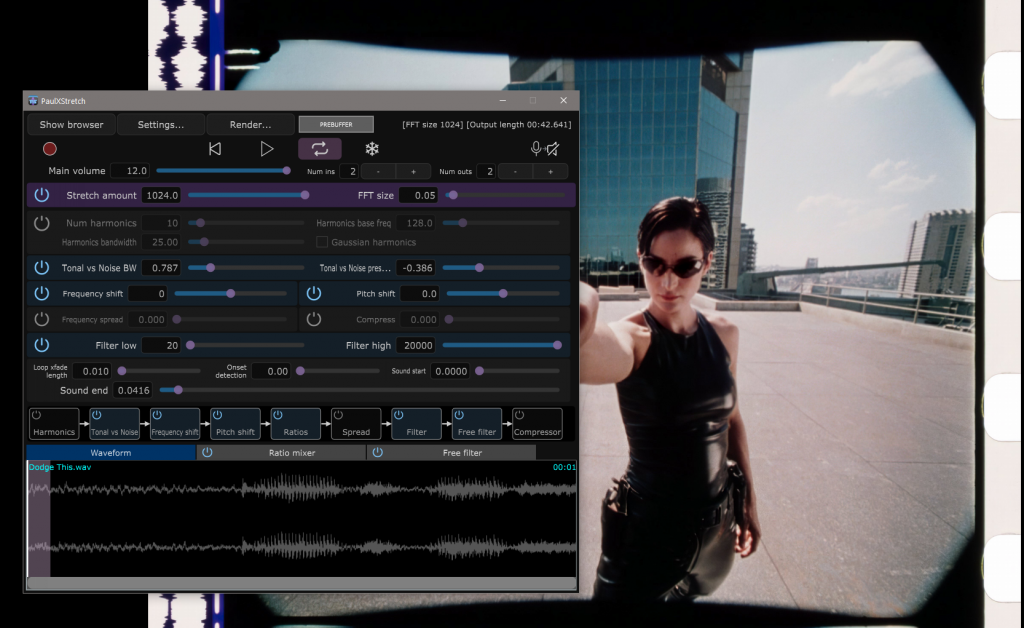

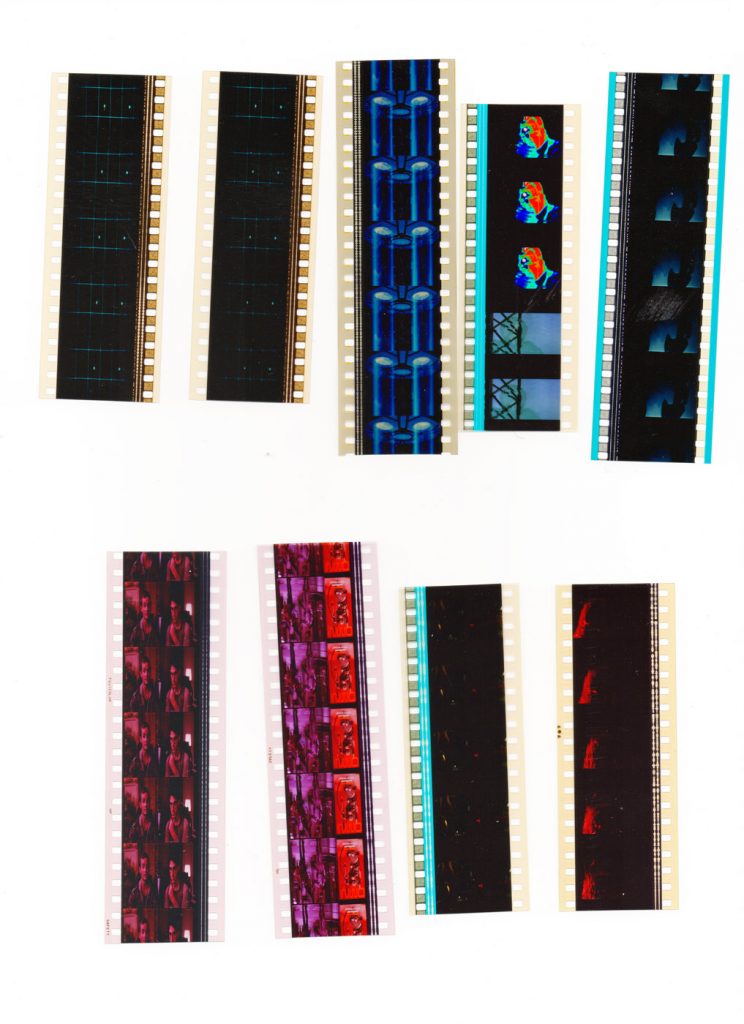

In July 2023, whilst attending a videographic workshop at Bowdoin College in Maine, I ran a small participant experiment exploring the embodied process of watching, listening, and responding to depictions of volume manipulation in films. This experiment invited participants to first view a short clip from the film Berberian Sound Studio (Peter Strickland, 2012). The clip in question features Toby Jones playing Gilderoy, an English sound engineer imported to Italy to complete the sound editing and mix on a horror film. In the clip below, we see Gilderoy begin playback of an elaborate tape loop and subsequently push the volume up on three faders on his mixing desk. For the experiment video, I replaced the original film soundtrack with some more easily identifiable sounds in the hope that these might be less distracting for the participants than the film’s original soundtrack.

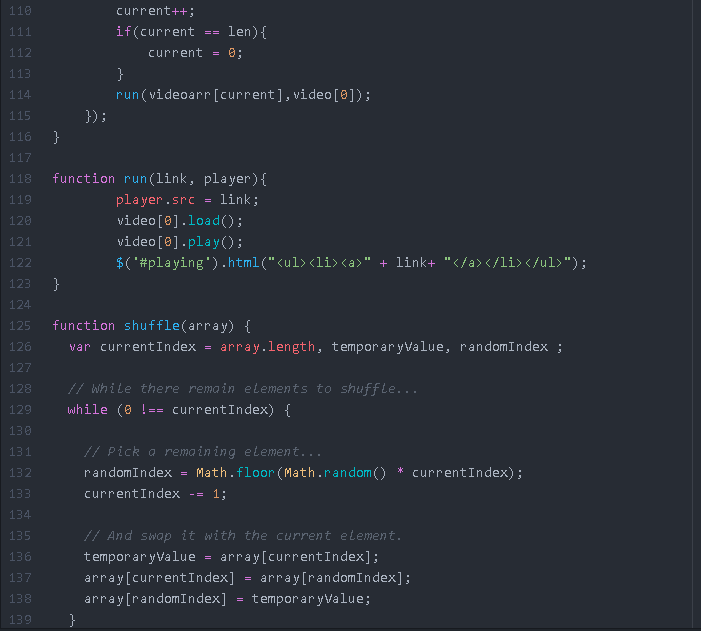

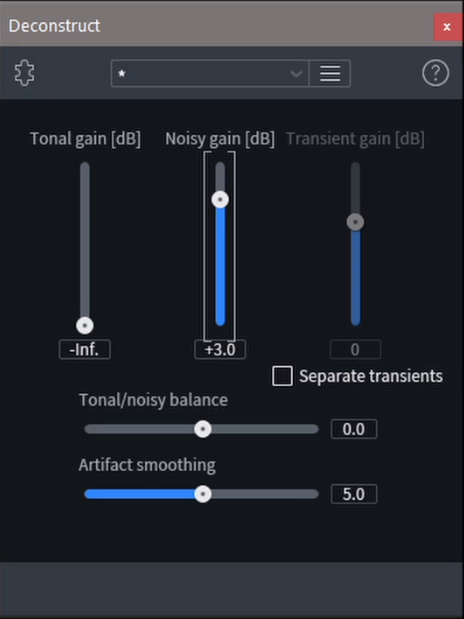

Using a small midi-capable controller featuring three-volume faders, the participants were then asked to re-watch the clip and attempt to mirror Gilderoy’s manipulation of the faders. Finally, the participants were asked to choose three sound effects from a pre-selected corpus, which they subsequently mixed in real time in any way they wished. Their performance with the midi controller was filmed, and the experiment was followed up with a short, semi-structured interview.

The video essay presented here is very much an in-the-moment response, completed within 48 hours of finishing the participant experiment. The work is influenced by Michel Serres research concerning the senses (2008) and by a paper by Eliot Bates in which he argues “that in order to understand the production of affect, or perhaps the affect of production, we need to pay attention to bodies, to the senses, to the practices of audio engineering and musicianship” (2009). In this video essay then I choose to pay attention to these bodies, and very specifically on the hands. Watching the videos of my participant’s listening and responding to their own audio mixes, I was fascinated by how expressive their hands were and how affective they were in these moments. The elegant, performative quality of the hand movements drew me towards an initial poetic engagement with the footage over any attempt to intellectualise the feedback the participants provided me (though this will feature in further outputs from the project).

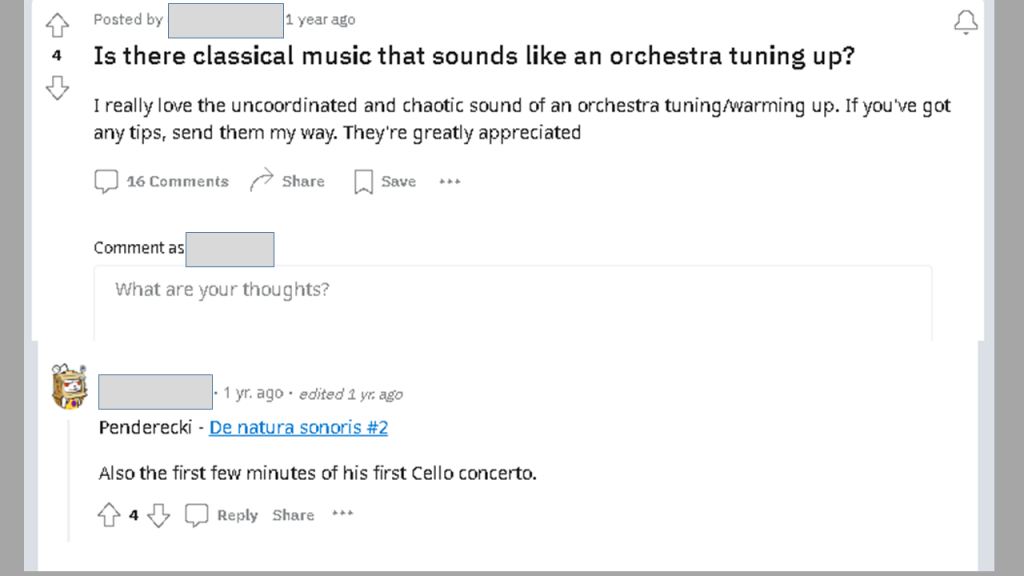

The decision to use Penderecki’s De natura sonoris no. 2 was almost entirely arbitrary, as I only stumbled across it when searching for the sound of an orchestra tuning up (which I initially thought might make a good background soundtrack for the work). As you can see in the final work, the music lent a guiding hand to the editing of the video, suggesting synchronisations with the performances and cuts in the edit, as well as lending a sense of uncertainty as to the relationships between the moving hands and the music; are they somehow acting upon each other?

Where Bate’s research centers on the expert audio engineer, I am observing here the novice, who may be mixing sound (at least in this fashion) for the first time. My goal though with this experiment was not to set out to learn anything new about audio engineering per se, but rather to see what I might learn about watching and listening to films. This experiment then attempts to create an embodied intervention between the viewer and the film, as Laura Marks suggests, to find “a model of a viewer [listener] who participates in the production of the cinematic experience” (2000). My aim was to place my participants somewhere between the on-screen action of volume manipulation and the reciprocal manipulation which this might precipitate during the post-production sound mixing process. And in this in between space they are both engineers and performers, novices and experts, viewers and listeners and, crucially, producers of something brand new.

References

Bates, E., 2009. Ron’s right arm: Tactility, visualization, and the synesthesia of audio engineering.

Marks, L.U., 2000. The skin of the film: Intercultural cinema, embodiment, and the senses. Duke University Press.

Serres, M., 2008. The five senses: A philosophy of mingled bodies. Bloomsbury Publishing.