Super Volume Supercut

If you’ve arrived here from the Super Volume page thank you for watching, I hope you enjoyed it (otherwise you can watch it here). You’ll find more information about the project in this post. An ongoing (hopefully growing) list of the films and television shows included in the supercut can be found at the bottom of this page.

Super Volume is a randomly generated supercut collecting instances of volume manipulation from film and television. Each time the web page is refreshed (or the Stop/Randomise button is pressed) the existing database of clips is reshuffled and a new version of the supercut is loaded into the video player. There is no rendered or final version of this supercut, rather it is designed to be added to as and when new clips are found and loaded into the database. This version of Super Volume is accompanied by (but not set to) ‘Gut Feeling’ by Devo. A ‘mute’ option is included on the page so that viewers can listen to music of their own choosing (or no music at all) whilst they watch.

Super Volume is the first part of a larger project to explore the specific relationship between the on screen action of volume manipulation, and the reciprocal manipulation which this might precipitate during the post-production sound mixing process, namely the turning up (or turning down) of volume. Functionally then, this supercut is as much about providing me (as a researcher) with easy access to the material I am working with, as it is about creating a new videographic work. But Super Volume is also an exploration of the process of creating a videographic work, of defining and designing an appropriate presentational mode, where publishing on Vimeo (where my previous videographic works all reside) might prove to be a limiting factor.

“Whether one thinks about the supercut as a database or a collection of images and sounds, it implies a process of aggregating and sorting that has no beginning and no end and that could continue indefinitely as long as there were new additional sources.”

Allison De Fren, 2020

There is no theoretical limit to the number of clips which can be added to the Super Volume database, but the intent here is not to be exhaustive, rather to be incremental. This particular mode of presentation means that the supercut is a perpetual ‘work in progress’, with no effective beginning or end, and no set length. My goal is that the project will grow through future collaboration as I develop other strands of research alongside it. The generative nature of this presentation mode also serves to curtail my creative impact on the final video. The process of careful editing and synchronisation which is often so intrinsic to the videographic form, and the supercut in particular, is stripped away here. The task of editing is reduced to ‘topping and tailing’ clips and nothing more (and as you will see, for the most part these clips have been quite tightly edited to the action). Whilst this does nothing to show off my editing skills it does make it considerably easier for me to watch (and re-watch) the piece. I have very little creative stake in how the work comes together, so I am inured against the agonising process of second guessing my editing decisions as I watch it back. Rather, I can adopt something of a duel position as both a cinephiliac, indulging my fetishisistic impulse to collect these clips, and as a dispassionate viewer, able to “maintain an objective distance” (De Fren, 2020) from this particular object of study, precisely because I have no control over the form it will take each time I hit play. Of course the lack of any agency on my part in the editing of the piece does increase the potential for it to seem ‘cold’ (Bordwell in Kiss, 2013). What labour might have gone into the sourcing of the clips, and the coding of the video player is not replicated in the careful editing, sorting, and syncing of the final videographic work. It remains to be seen whether other viewers take anything away from the viewing experience, or feel the need/desire to explore the potentially endless random variations available to them.

I have already watched Super Volume a lot, at first to refine the code for the video player (more on the technical aspects of this below), and then to explore just what the random nature of the supercut might reveal to me. I intend to write more on this in the future, but initially I find it interesting to note how differently each hand approaches this seemingly simple task, disconnected as they are here from any narrative context (and body) which might clue us into their motivations. Some are hesitant, questioning, whilst others are definite, casual, happy even? Most are white and male, which I could suggest is indicative of the nature of the films and television shows where I have harvested these clips from. But implicit in that suggestion is my own potential bias, directing me to specific sources in search of these clips. Either way I am in need of a much broader sample of clips before I can make any meaningful analysis, and I am hopeful that the open and ongoing curation of the project will help with this.

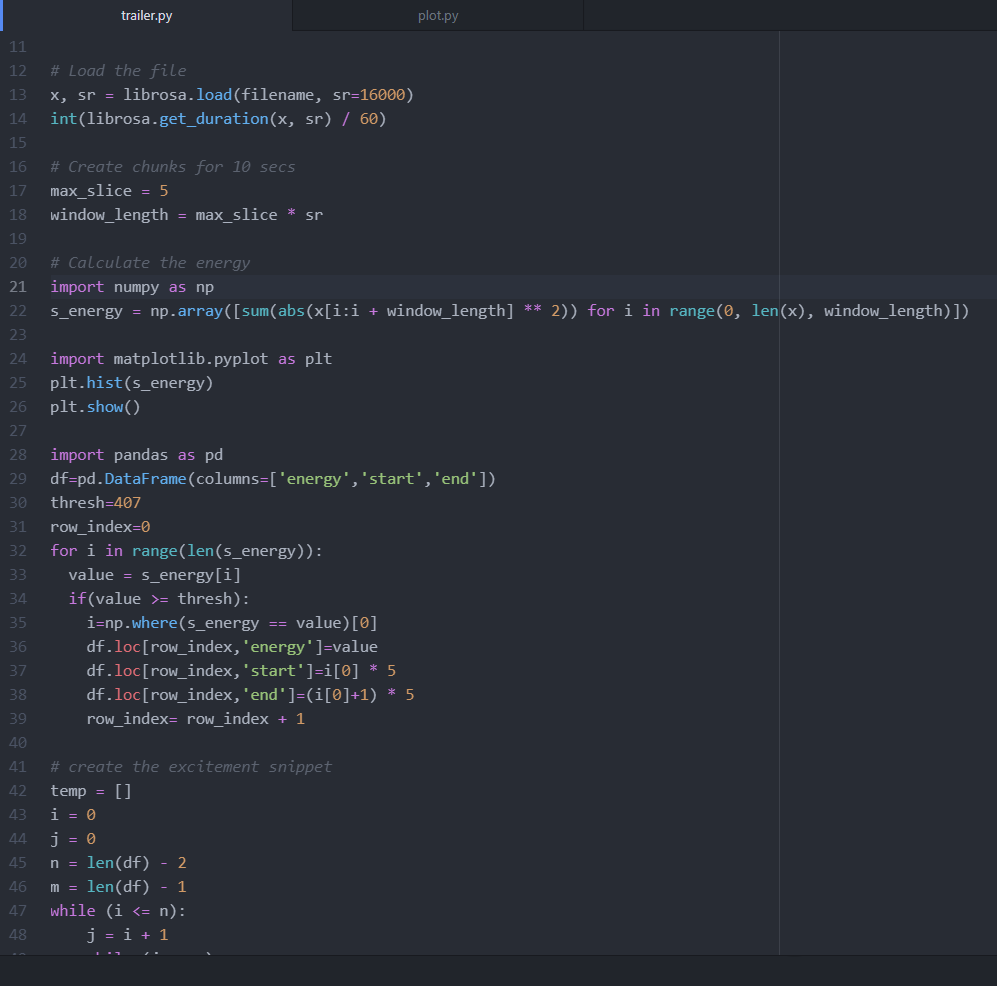

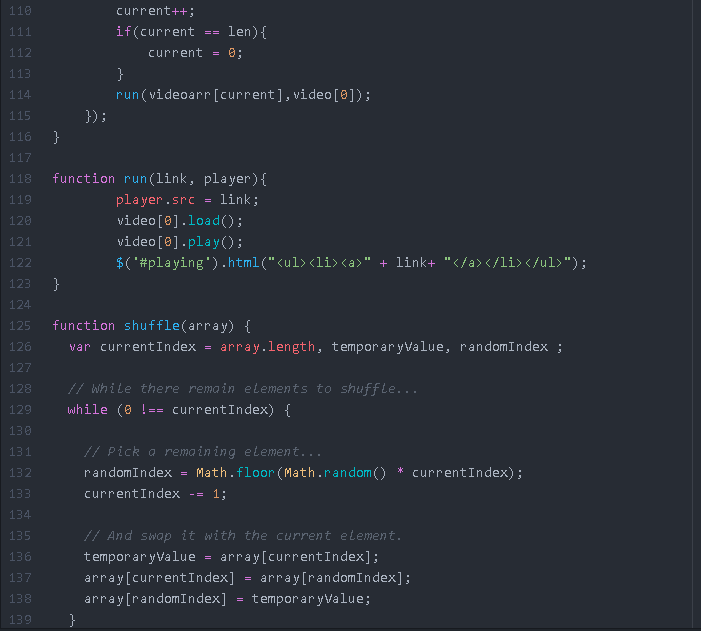

The Super Volume player is based on this code by Ben Moren. Ben was kind enough to help me out with a few tweaks to the code despite it being quite a few years since he wrote it. Getting a video to play back in a modern web browser is a reasonably straightforward process, but finessing the functionality for Super Volume took quite a while (largely because I am not a coder). The Super Volume player is actually 2 video players stacked on top of each other (thus it takes a little longer to load than a normal web page). The transition between videos clips is the 2 players swapping places, one moving to the ‘front’ (in Z space) whilst the other loads the next video. The supercut will always start with the same 2 video clips so to avoid obvious repetition, I have added two short, blank videos as clips 1 and 2. Ben’s original player code already handled the random shuffling of the clips into an array for playback, but it needed a small tweak to stop it playing the clips more than once in what was essentially an endless loop. Now the video player will stop after the final clip in the database is played (though the music will continue). The Stop/Randomise button re-loads the webpage, running the code again resulting in a newly shuffled array of video clips, and a new version of the supercut.

Special thanks to Alan O’Leary, Ariel Avissar, and Will DiGravio who provided invaluable usability testing and feedback on the first version of this project.

This is the first part of a larger project which I anticipate will run for at least 12 months and more on that will be published through this blog as it comes to fruition. If you have any thoughts, comments, suggestions, or questions about Super Volume please email me at cormac@deformativesoundlab.co.uk

| Film | Number of Clips |

| Upstream Color (2013) | 1 |

| Talk Radio (1988) | 1 |

| Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018) | 2 |

| Back to the Future (1985) | 4 |

| Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989) | 3 |

| Ali G Indahouse (2002) | 1 |

| Studio 666 (2022) | 1 |

| Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) | 1 |

| Caddyshack (1980) | 1 |

| Berberian Sound Studio (2012) | 8 |

| Airheads (1994) | 2 |

| Bill & Ted Face the Music (2020) | 1 |

| Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) | 1 |

| Blow Out (1981) | 1 |

| Deadwax (2018) | 1 |

| Spiderhead (2022) | 1 |

| The Gray Man (2022) | 1 |

| The Last Word (2017) | 1 |

| Things Behind the Sun (2001) | 1 |

References

de Fren, A., 2020. The Critical Supercut: A Scholarly Approach to a Fannish Practice. The Cine-Files, 15.

http://www.thecine-files.com/the-critical-supercut-a-scholarly-approach-to-a-fannish-practice/#_edn10

Kiss, M., 2013. Creativity Beyond Originality: György Pálfi’s Final Cut as Narrative Supercut. Senses of Cinema, (67).

https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2013/feature-articles/creativity-beyond-originality-gyorgy-palfis-final-cut-as-narrative-supercut/

Other reading/watching

Meneghelli, D., 2017. Just Another Kiss: Narrative and Database in Fan Vidding 2.0. Global Media Journal: Australian Edition, 11(1), pp.1-14.

https://www.hca.westernsydney.edu.au/gmjau/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/GMJAU-Just-Another-Kiss-Narrative-and-Database-in-Fan-Vidding-2.pdf

Tohline, M., 2021. A Supercut of Supercuts: Aesthetics, Histories, Databases. Open Screens, 4(1), p.8. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/os.45